BACKGROUND

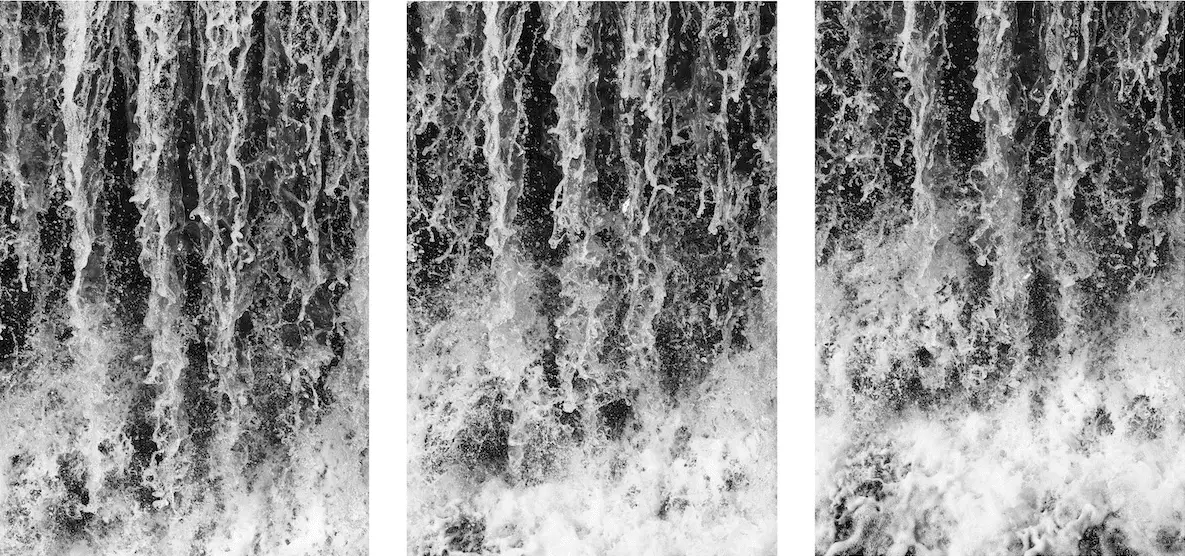

Artists have always sought inspiration from the natural environment, and perhaps never more so than during the Romantic era. Against the backdrop of the Industrial Revolution when ‘unspoiled’ nature was deemed under threat, and when humanity seemed small and insignificant against the raging rivers, waterfalls and violent storms, the pastoral, sublime, and picturesque came to the fore.

‘The space the magnitude of mountains and waterfalls. I live in the eye, and my imagination, surpassed, is at rest. I shall learn poetry here’.

So writes Keats on his walking tour of Scotland. Taking a grand tour of Scotland and visiting the spectacular waterfalls, became a national obsession with Turner, Walter Scott, Byron and Burns all leading the vanguard.

So writes Robert Burns in 1787; –

‘After breakfast we made a party to go and see Cauldron Linn, a remarkable cascade in the Devon basin, and after spending one of the most pleasant days I have ever had in my life, I returned to Stirling in the evening’

Burns went on to write numerous poems inspired by waterfalls, as did Byron and Millais and numerous others including; Wordsworth; Louis Stevenson and Mendelssohn, who all wrote about them. Consequently the great British public, visited them in droves.

Since those heady Victorian days the paths leading to well over 1000 waterfalls, have become overgrown, and many falls have all but disappeared from our maps.

Now against the backdrop of climate change and a global pandemic, there has never been a more urgent need to reconnect with nature.

Waterfalls now invite contemporary and ecologically aware authors, artists, and poets to connect with nature in much the same way as their romantic counterparts did.

Be it in the form of a simple diary entry, a social comment, poem, or haiku, author’s work including that of; Kathleen Jamie; Jen Hadfield; Anthony Vahni Capildeo; Cal Flyn; John Glenday; Malachy Tallack; Amanda Thomson; Elspeth Wilson; Ceitidh Campbell and Marjorie Lotfi, together with specially created images by artist Oscar Van Heek, formed part of a major exhibition at The Scottish Poetry Library during the Edinburgh Festival ’23. The work will subsequently form the basis for a major publication which will contain text from both the contemporary and the romantic authors, poets and artists.

PRINT SALES: Limited Edition, signed hand printed images are available. Contact [email protected] for further sales information and delivery.

MASPIE DEN

KATHLEEN JAMIE

I am here tae tell ye I never lie

at peace I am aye

caller watter jining watter

pirl an ongang

alang ma a bed of clabber

I obtemper ainly gravity

an here I come

a rinnal amang bracken, I slocken

deer drouth, I run

eident atween hazels and thrangs o rashes

until the meenit oh the meenit

I jist

skail, I just

skail ower

the skelf o stane

an I am ane

blythe spangle

i the sunshine ane

siller flash

ablow the mune and then it’s

ower sae

I splash

an haud on doon through the laigh kintra I cannae help masel

it’s back tae ma

hurl and gush but

see thon memory thon

sweet memory I cairry it

richt wi me tae the sea

GLEN VALE

MALACHY TALLACK

In this scooped out place, this hollow in the hill, the world contracts. A tattered white ribbon arrives, fizzing as it falls. The amber plunge pool, a battered drum, drowns out all other noise. Around it, the narrow bowl of soft stone, quarried by water, has been witnessed and signed, initials engraved with knives and fingernails. The rock is carved and carved again, peeling, flaking, crumbling. Notches become pockets become smooth craters. Names are etched and then erased. The burn, continuing, carries what it can. It is an amnesia, a ruthless erosion. Only the sound and what is most solid will remain.

WOODSTON BURN

JOHN GLENDAY

Though the farmer took it for a scar

cutting a zigzag through his land

and little better than an open drain, still

it would bring that heady reek of gorse

and primroses in their proper time,

a stonechat or two challenging the air

and the burn itself, of course, muttering

as it worked, because it understood

there are some wounds only a river can heal;

so busy enough before that final graceful

plunge back down towards the beginnings

of things; though when I say beginnings

there was only the roofless cottage,

rocks then sand, and over our shoulders

the North Sea, filling with light.

BLACKSPOUT

ELSPETH WILSON

Wreaths of cloud wrap themselves around trees, strangling or snuggling them so tightly that we can only see them as a suggestion. A question mark in a hushed landscape, as water rushes, hushes, downwards. We could fall asleep here, on the blanket of snow that has transformed a car park into a grotto, the lullaby of Blackspout crashing into our ears.

But we walk. We learn to eke out the colour from the landscape, which at first appears monochrome. Feathery green lichen coats branches, a plant we think is dogwood shows its deep red stems. Ruddy bracken frames our view of the frothing water, crashing down with such power it almost scares us. The snow makes light of a gloomy day. Green undergrowth and russet leaves peek out in patches, wondering when winter arrived.

Above the cascade, smaller falls pour into pools, like they are practicing for the main race. A nursery for the water before it can fly.

When we cannot see it, we can still hear it. When we can no longer hear it, our ears ring with the silence. Like a parent, there is presence in its absence.

We wonder when a droplet in the candyfloss mist ceases to be the waterfall itself, ask ourselves when does it become separate, when might it become part of the whole again. Is there a moment where you know what you’re a part of and what you’re leaving? We wonder.

BURN OF TACTIGILL

JEN HADFIELD

on me?

its leg

constantly cock

let it

this waterfall in my

can I keep

and slimy

green streaming

to their anticlimax

but follow

I have to jump

every time

a showpony

I baulk like

everything

drowns out

actually

but their muzak

lately

things very seriously

I have been taking

&

of the burn

little rushes

soaked by

black moss

a merkin of

chandelier

as an airport

the bathroom

hang it in

like a bead curtain

would be to wear one

perhaps a good look

pouring light?

with their rods of

how would you paint them

the giggles

a fit of

tummy

a rumbling

all night long

don’t blub

it isn’t that they

into a glass

plonk

strongly glugging like

cups in their

chatty

are the most

little waterfalls

sometimes the

FAIRY GLEN

CAL FLYN

At midday it’s still cold in the dell. It’s shady here, protected from the breeze. It feels like another climate. The mill pond is a sheet of ice, which gives off a matte gleam. Dry leaves lie in drifts against fallen trunks, dusted in a frost of powdered sugar. Above: a silver gelatin sky. Clouds passing overhead as negatives, the dark criss-crossing of branches without their foliage.

At the falls, the water streams over the rocks, churning to a froth, white as milk. The fairies that gave the glen their name were said to work here, purifying the stream for use by the houses downstream. Villagers left offerings to them: a piece of bread, a bell. There are spots where one can imagine a fairy reclining in comfort: boulders cushioned with soft mosses, shallow pools in which a dainty figure might bathe.

In winter it’s quiet. Only a few shrill birds break the silence. The leaflitter is springy and wet. A hibernal colour scheme of tan, dun, grey—but here and there, there are bright spots: firm round fungi protruding from a tree in shades of tangerine, papaya. Rhododendron clambering over the low ground, spreading plasticky green leaves.

At the foot of the valley the path is packed earth, wrinkled by roots, which press up through the dirt. They are thick, muscled, sinuous. Generations of lovers have etched their initials into smooth bark—letters that have stretched and warped with the passage of time, as the trees have grown, scarred over, filled out.

As, of course, have we. The last time I was here I must have been seventeen. The broad strokes of me were drawn by then, but oh how they have bent and changed. To come here is to pass myself upon the path, walking in another direction.

AFTER GREY MARE’S TALE

MARJORIE LOTFI

As with everything, from below

the waterfall is only an arc, the pound

against stone, from below it’s all

roar. At the pool’s edge the surface stills

and clears to peat water, the ledges

make entry possible; but you

are watching the tail of the mare shift,

swollen, in spate with winter.

The whole body of the burn runs

and stands still. As with everything, the truth

is out of sight. Walk towards it by

first walking away –

a flooded track, the season’s mud

almost ankle-deep – and clamber up

the stones, slippery with weather.

Then turn your body back at this angle.

From above the snake of water Is silent

across its bed, waiting for the brink.

Plunge your hand into the flow

at the point of drop and gauge

how much earth has given way,

how much still holds its ground.

See how small a thing can make

this noise from the sheer act of falling?

BLACK LINN

ANTHONY VAHNI CAPILDEO

A waterfall cannot be anticipated

even when you go towards it; when you carry

its name over bridges, through glacier-dozed landscapes,

under your skin; a waterfall can come only,

ideally, resistless, lighting its home by rocks

that yield, giving up their gleam, yielding to softness

water is – the force water has; a waterfall

cannot be anticipated – we invite ourselves,

it visits itself on us, and we let it

carry its name away from us. For it is first

amidst whatever else is happening, leaping

of fish, restyling by frost, disrepair; urgent,

like the waterfall you make, my first truthful eyes.

Many delights attend the walk to Black Linn from Dunkeld, and I delighted in them, while half-dismissing them as so many distractions from the goal of my quest – the waterfall. Dunkeld Cathedral was bright in the winter sun. St Columba’s bones, brighter yet in the imagination, lie buried under the blue-carpeted stairs. Danger! Signs warned of falling masonry. A shower of stones could come from the sky while you looked up thinking of salvation., or looked down, wishing the building whole again Netted-off areas mourned the forest-like community life that cathedrals anciently are meant to foster.

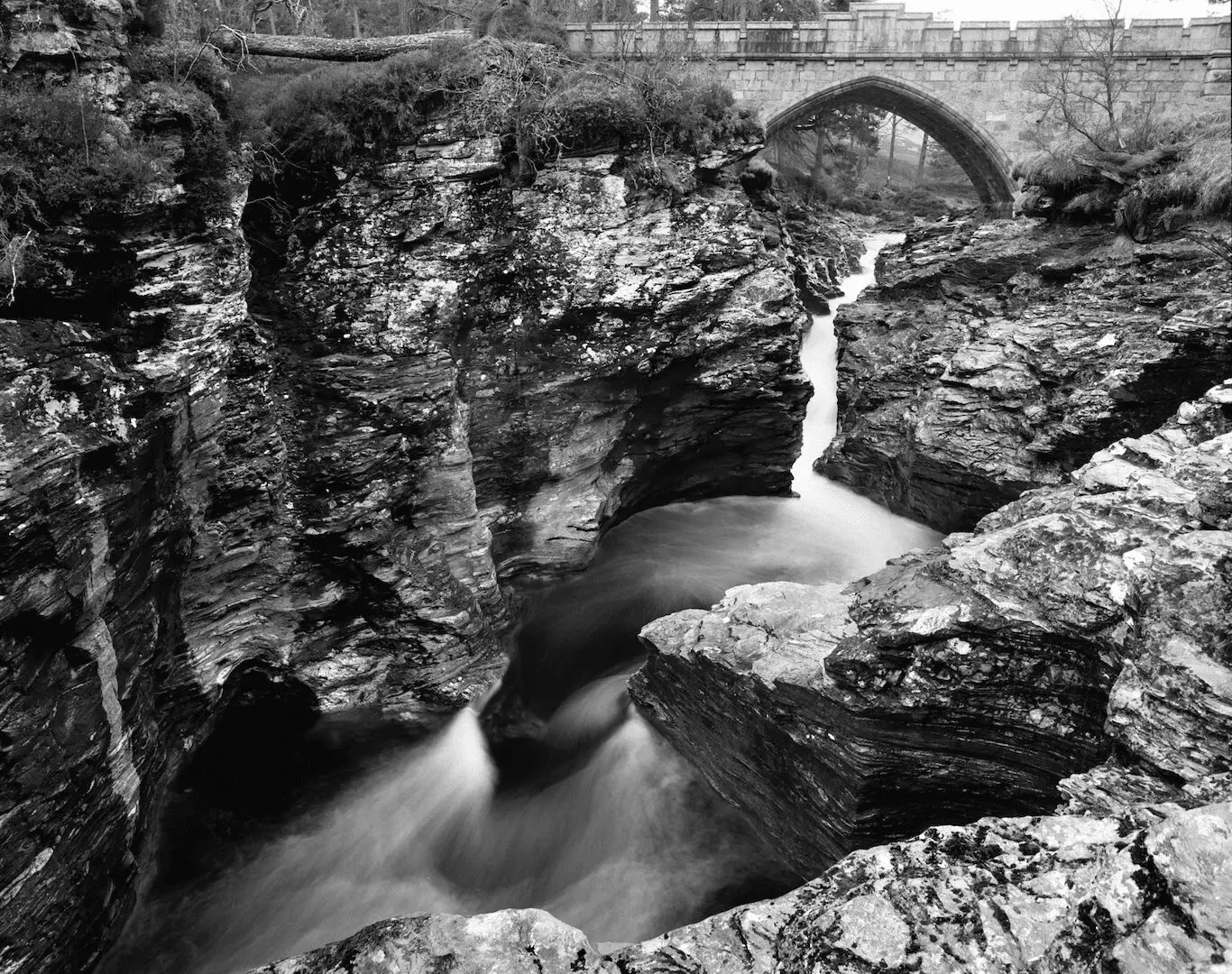

The Cathedral is on the other side the River Tay. You need not go so far. Instead, you could wander towards the Hermitage and Black Linn along the River Braan, trying to forget a thousand thousand old poetic references to the wild wonder of salmon travelling upstream. Here, in autumn, you may see these jumping crescents of muscularity attempting to ascend the falls.

It is winter. Salmon are not leaping. Frost sparkles and crunches in the mud underfoot. This is the Land of Tall Trees. If this is the kind of woodland that Shakespeare’s Macbeth imagined marching on Dunsinane, the terror would not be that trees are walking, but the height of the trees, walking. They would fill up the imagination. Nothing else would be imaginable. Little else would be visible than their fragrant, spindly confidence on the move. I loved pattering along these pathways, an undersized creature. Nonetheless, I would not be distracted. My goal was water, in movement downwards; not Douglas firs, at ease almost among the clouds. If ‘Ossian’s Palace’ is open, you can step in to be dazzled by the folly’s mirrors. I did not.

The power of Black Linn is both gentle and astounding. The smoothness and shine of the surrounding rocks, jet-black, testifies to how the waterfall has planed them, creating a channel for its needs. I lean over the edge and see narrow folds holding caves. The sound of the waterfall, described by many visitors as thunderous or crashing, was (for me) profoundly peaceful. Even an easy walk stirs my mild asthma, mixing my perception of inner and outer; alongside birdsong, I hear my body’s obstructed piping. Now, as I rest at the edge of Black Linn’s huge, incessant orchestration, it is as if outside and inside are gentled back into tune. I am centred, seeming to become through and through waterfall.

Then I walk a little further. The path bends. The view changes. The stone bridge becomes an arched brow, framing the Black Linn’s ongoing look. It is a romantic view – ever new, like a beloved’s gaze; long sought, innocently surprising.

THE FALLS OF FOYERS

CEITIDH CAMPBELL

Making its dramatic entrance

cascading over the shelving slope –

glen and village carved out

by the torrent.

Kelvin outraged nature

in the name of progress

stealing the celebrated vista

of kings and poets.

Making an industry of the falls

transforming water into electricity,

a black smelting pot

instead of a hellish boiling cauldron.

Every sheet of aluminium

reflecting the journey to the loch,

strong and everlasting

like the source of its power.

THE FALLS OF TRUIM

AMANDA THOMSON

From the headstreams that flow from the hillsides of An Torc and Creagan Doire Dhonaich and run northwards through the Drumochter Pass and into Badenoch and Strathspey, the river Trium starts. It gathers the scriddens and torrents and streams and the invisible waters that this porous land leaks. The Truim riffles and tumbles quietly, unobtrusively, along its namesake glen, running parallel, for the most part, to the railway line and the A9, each of them a north|south artery up and down this land. A scant few miles from its beginnings, and after a drop of over three hundred metres already, the river becomes, briefly, the falls of Truim, which some might quibble are more a series of rapids than a true linn. Perhaps, seeking a waterfall, some might feel they’ve been mis-sold, but bear with me.

These falls are quite hidden, and your first encounter of them might be from peering over an old stone bridge originally built by General Wade’s men in the 18th century. They’re not one of these places where you can go to a single viewpoint and see the whole of them. So go down through the birch woods to the water at the eastern side, and clamber along the banks, over where flat ferns spread, verdant green, and mosses, liverworts and lichens cling to the rocks and cover fallen branches and trees. In comparison to other waterfalls, these might seem quite modest, and they’re all the more intriguing for that. There’s not a single fall here, a single tumble, or indeed, any drop of spectacular size. Instead, it’s a series of trips down, and in-between them the water gathers, slows and swirls and, consequently, because of how you can view them, and what you know of where they come from and where they go, it’s hard to separate the falls from the before and the after of them. It’s a mixture of the hard and soft here, in rock and vegetation. Granite shelves lie sharp and rise quite high in places, sometimes bare, sometimes easing back into landscape with thin coatings of mosses, then heathers, ferns, birches, pines. Lower down, the rock is smoother, water-worn over millennia.

Where the water tumbles, the granite constricts the water into narrow channels, making it splash and gurls and froth in golds and straws and ambers as it falls and decompresses again in wider, deep, dark pools where it will marble and circle around, ever closer to the next narrowing channel and fall. There are pools here so deep that they will catch and hold you if you jump from the five metre ledges that overlook the water (I’ve seen it done), and these same pools that sometimes seem languid will quicken and rush directly on in spate, hurrying its waters towards the point where the Truim meets the Spey, the second longest river in Scotland, reaching the sea 100 miles north east from its own headwaters.

I read that Glen Truim means ‘the glen of the elder tree river’, though at the falls, my memory is only of birch, Scots pine, and larch. Other surrounding place names hint at what else you might encounter. Drumochter means high ridge, Badenoch itself means the flooded place, and just a few miles downstream, beyond where the Truim and other tributaries join the Spey, you’ll come to Insh Marshes, a 1000 hectare flood plain, insh meaning, the low-lying land near a river, and at the moments when the Spey has burst its banks, you might wonder how the vast loch before you could ever be anything else.

This is a place not just to encounter the falls and the water, but to take in and become part of its sounds, smells, colours, textures and everything else too. The birdsong you might catch above the rush of water. The sparks of larch at the turn of autumn and, at that same time, the green gold yellow rust of changing birch leaves and how they fall into the water, swirling around and revealing its currents and eddies; how a root of a Scots pine binds itself tightly to a vertical granite face, reminding you, perhaps, of the tendon of a climber’s finger, clinging to the most precarious of holds. How the shallower water is more of a Speyside amber that deepens to the colour of an island malt, and how the deep pools are the colour of a wet peat bank and even darker still.

And if you’re lucky, and there at the right time, you might just see a salmon leaping upstream, heading back to its spawning ground, and you might wonder and marvel at its journey from sea to the Spey to the Truim and up beyond these falls. Or you might glimpse an eagle high above heading south to the high peaks and ridges of Drumochter, towards the headstreams that start the river Truim’s journey, or northwards to the Spey.

THE CAULDRON LINN

ROBERT BURNS

In a letter written in 1787, Robert Burns described a visit to the Cauldron Linn:

After breakfast we made a party to go and see Cauldron Linn, a remarkable cascade in the Devon about fives miles from Harviestoun; and after spending one of the most pleasant days I ever had in my life, I returned to Stirling in the evening.

The falls that once used to be on everyone’s itinerary, are no longer marked on any maps, and they are awkward to reach because the paths are overgrown. The best approach is from Muckhart Mill, but they can also be tackled from the footpaths along the spectacular Devon Valley Railway.

LINN OF DEE

LORD BYRON

At the Linn of Dee the river narrows to a little over a meter in width. The channel is cut in schistose rocks and below the present falls there is a series of round pools. Downstream is a small dyke that probably marks the site of the original fall. It is possible when the water is low to step across the stream safely however it was here that young Byron caught his lame foot and was saved from a fatal fall by a companion.

In the course of one of his summer excursions up Dee-side, he had an opportunity of seeing still more of the wild beauties of the Highlands having been taken by his mother through the romantic passes that lead to Invercauld, and as far up as the small waterfall, called the Linn of Dee. Here his love of adventure had nearly cost him his life. As he was scrambling along a declivity that overhung the fall some heather caught his lame foot, and he fell. Already he was rolling downward, when the attendant luckily got hold of him, and was but just in time to save him from being killed.

Lord Byron his letters and journals by Thomas Moore

The ornamental granite bridge at the Linn of Dee was opened by Queen Victoria in I857

THE FALLS OF BRUAR

ROBERT BURNS

In the late summer of 1787, Robert Burns set out on a tour of the Scottish Highlands. He had been invited to stay at Blair Castle, by the fourth Duke of Atholl; his lordship advised the poet to be sure to make the detour to view a local beauty spot, the necklace of falls known as Bruar Water.

Burns loved the falls, and declared later that these two or three days were the happiest of his life. He found Atholl picturesque and beautiful but was however critical of the lack of trees and shrubs. In true Burns style he wrote a poem to the Duke of Atholl, begging him to re-vegetate the treeless hillsides.

His poem with its jaunty characterisation of a highland stream provides a splendid memorial of his visit:

Would then, my noble master please

To grant my highest wishes,

He’ll shade my banks wi’ tow’ring trees

And bonie spreading bushes.

Delighted doubly then, my lord

You’ll wander on my banks,

And listen monie a grateful bird

Return you tuneful thanks.

Excerpt of Burn’s poem ‘The humble Petition of Briar Water’

The duke took note and the larch woods for which his estates became famous were created by Duke of Atholl, who became as known as the ‘planting duke’.

FALL OF URRARD

An ancient stone in the grounds of Urrard House marks, if local tradition is to be believed, the spot where Dundee received his mortal wound at the Battle of Killiecrankie. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-82), the Victorian poet who almost completely lost his reason in middle life, was taken to Urrard House for a period of rest and recuperation.

Near Urrard House is the beautiful Fall of Urrard. The fall was frequently visited by the Victorians, but has since received very little notice in guide books since Black’s Guide of 1861. It is not marked on any map, and it is a very good example of the way in which scenes which delighted the Victorians, are neglected. Today the fall is marred somewhat by a hydroelectric scheme at the side of the falls.

FALLS OF FALLOCH

Dorothy Wordsworth

At the principal fall, the water plunges over a rock lip into a basin, the main stream falling ten meters sheer. This is Rob Roy country and the basin is dubbed Rob Roy’s Bathtub. A smaller hollow, etched by a lesser arm of the stream in the wall of the basin is called Rob Roy’s Soap Dish although it is unlikely that the famous raider and cattle thief used that commodity when in these parts.

Many writers of whom Dorothy Wordsworth is perhaps the most famous, have celebrated the falls at Glen Falloch. She gives a memorable account of her walk to the falls with her brother, William, and Coleridge:

We sat down and heard, as if from the heart of the earth, the sound of torrents ascending out of the long hollow glen. To the eye all was motionless, a perfect stillness. The noise of waters did not appear to come from any particular quarter; it was everywhere, almost, one might say, as if ‘exhaled’ through the whole surface of the green earth. Glen Falloch, Coleridge has since told me, signifies the hidden vale; but William says that if we were to name it from our recollections of that time we should call it the Vale of Awful Sound.

Nowadays the falls are a notable wild swimming spot though not without danger particularly when the falls are in spate.